|

Talking Dharma – Talking Secular Awareness

Awareness has become quite the buzz word in so many different fields these days. You will find it being spoken of when engaging in any different forms of psychotherapy. You’ll find it being promoted in schools, in corporate business, the sports world and even the military. It’s quite amazing really that something the Buddha spoke about 2,600 years ago as a method to reduce or eradicate worrying has taken so long to take off. The possible reason for that could be that when the Buddha talked about it he mentioned that it needed to be developed with integrity by living within a particular framework of ethical principles. When you explore the different fields it is now being used it begs the question are they getting the real deal or a counterfeit version? The education system in many western countries appears to be one of competitiveness and the fight to be the best at all costs. Do you have a sense that corporate business has a focus on ethics? What about the military? Programs vary widely, of course. Some have a firm foundation in the Buddha’s teachings while others make no reference to Buddhism in order to strip it of its spiritual context. Exploring this question naturally leads to another: what is the awareness of the Buddha? The Buddha taught that worrying arises out of the confusion of the conditioned self-biased mind that exists on the basis of conditioned subjective reality and does not see the actuality of things. What he sets out in his communication is a developmental journey where we can begin to unpack experientially the four principal assignments within our moment by moment experience as we walk the eight-fold journey. It is within this journey where we can work in meditation on realizing insight into the three characteristics of actuality: 1. The existence of worry. 2. Impermanence 3. No-thing-ness. To be in a position to develop conscious awareness so that we are aware of the motivational intent behind everything we think say and do is the freedom the Buddha offers, for us to take 100% personal responsibility without recourse to blaming others or external events. Here we are working to alleviate and then eradicate the drives of want, not want and confusion that keep us trapped in cyclic patterns of habitual thinking, speaking and acting which results in a worrying mind. Possibly the most significant tool in the Buddha’s toolbox is the development of awareness, which is the ability to be consciously aware in each moment to what is happening physically, emotionally and psychologically within the entire mind/body complex. The primary method he suggests is through the concentrative meditative process in such practices as the awareness of the breath that eventually extends to open awareness, and the awareness of kindness, that eventually extends to compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. To compliment these formal practices he encourages effort in the areas of ethical conduct, generosity and simple living. Combined together this is, in effect the whole of the eight-fold journey of the authentic Dharma practitioner. Awareness practice, both in and out of formal meditation, helps us to go beneath the surface level of our moment-to-moment life experiences, which are habitually clouded with unhelpful emotional reactions and provides the greatest opportunity to see through those conditioned habits so that we can see directly and clearly the actuality of what is happening. In our day to day life, awareness helps us see clearly what needs to be done. It helps us to understand what we are capable of doing, and how that will be of greater benefit to the development of our Dharma life. What most distinguishes awareness as taught by the Buddha from the types of awareness techniques that are out there in the commercial market is that he does not teach it as a standalone skill. He teaches it in conjunction within a structured and self-supportive development that is supported further by others who are also making the same journey. It is there firmly embedded as one of the themes within the eight-fold journey itself which is of course the development plan he suggests that will result in the breakthrough awakening moment to the actuality of causality. Awareness supports the moment-to-moment intention to do the least amount of harm to yourself, others and the world around you and to let go of the unhelpful worrying mind so you can develop and maintain a helpful mind state that will be at peace with itself, others and the world around you. It is awareness that helps us to engage with integrity the other themes within the eight-fold journey such as emotion, speech, effort, livelihood etc. Awareness as a stand alone practice may well lack the ethical and inspirational qualities that come as the complete package on offer by the Buddha. There is one thing to be aware of because it is often suggested, within Buddhist texts, that awareness is always conducive to developing a helpful state of mind. But in actuality the development of awareness can, if it is not supported by ethical practice, also provide opportunities where we can gain an advantage over others or be in a position to manipulate them in some way. Clearly this was not the Buddha’s intention or position. No matter what the circumstances are in which it is taught, it is clear that awareness is a helpful tool when it is based in sound non rule bound ethics. It creates focus, clarity of thinking, reduces or eradicates the worrying mind and provides the opportunity to develop contentment and peace of mind. It helps to maintain that helpful mental state and this, after all, was the only reason the Buddha communicated this and everything else he taught. Awareness, within a Dharma context has one objective only. To eliminate the worrying mind and replace it with a mind that is at peace with itself, others and the world around it. When living on the basis of conscious awareness we are walking the Dharma journey alongside the Buddha and embracing with integrity the gift of the Dharma he gave to us. Awareness is a valuable tool that can be helpful to highlight blind spots. At the centre of what the Buddha communicated is the practice of getting to know, with integrity, the unhelpful aspects of the journey so that we don’t have unhelpful and reactive stuff going on as a part of our experience. This is what the blind spot is all about. Another very important aspect when bringing awareness in is to be aware of our tendency to cling to our habit of re-conditioning our self-biased minds by building and managing a persona as if it was a real, solid, consistent, enduring, unshakeable thing. Have you ever found yourself acting more calm than you actually are, or of veering away from admitting unhelpful behaviour, or of discussing the unhelpful, as if you're above that now? If so, you may be well having the experience of a blind spot. The worst thing about the blind spot experience is that it is so self-sabotaging because it is actually a really big hindrance to authentic progress. What are its symptoms? There are many, but a few of the most general ones to watch out for are a tendency to use Dharma practices as a means to avoid dealing with uncomfortable experiences, old wounds, unresolved hurts or any other worry that is preventing peace of mind being realized or maintained. Often this materialises as a withdrawal from ourselves and others by hiding behind some metaphysical belief aspect that can seem so appealing at times when worrying is at its most active. This often results in an exaggerated gentleness, niceness and superficiality. To be fair, this is most common within classical Buddhist schools and its adherents and possibly our secular western approach does not give us so much opportunity to do this, but I have to say I have witnessed it quite strongly within western Buddhist circles. Other symptoms include exaggerated detachment, emotional numbing, repression and overemphasis of the positive or overly tolerant compassion all of which will only ever lead to a lop-sided development. If we are not bringing awareness to what is actually going on within our experience, Dharma practice can very quickly become a defence mechanism that allows us to rationalise or justify unhelpful thoughts, speech and actions that we engage in. When we find ourselves having a hard time maintaining our individual practice do we reach out for yet another Buddhist book, or another you tube video and think to ourselves that it is really helping us in some way? Is the answer to our worrying in that book or video, or in this thing we call mind that we are avoiding confronting? Playing the game of the Dharma life gets you nowhere. You can pretend all you like that you are someone who is constantly at peace with yourself, even though what is actually happening seems like the weight of the world is actually crushing you, but all that does is make you more and more inauthentic. When blinded it is so easy to deflect personal responsibility for maybe saying or doing something hurtful to someone else because somehow you think they need your advice, or you find yourself just uttering a Dharma cliché such as “it’s all an illusion” or “it is what it is.” Being aware of a blind spot is no easy task because the self-biased mind is invested in always being right and will go to great lengths to convince you that you are far more advanced than the rest of your peers who you tend to see as slackers. If you ever find yourself having those kind of thoughts, it’s time perhaps to remember that it is not a part of your practice to judge the practice of others and to start taking a little more responsibility for your own. The blind spot is about taking a phrase based in reality such as “it is what it is” and using it to ignore our own subjective reality such as the grief we experience at times of loss, or the remorse or regret we experience when we have not been at our best ethically. What we need to be doing is repeating to ourselves often, on the personal and interpersonal level is that it’s actually OK not to be OK and that’s OK. This is where integrity comes into play. Before we can actually deal with our worries we have to be honest about them and accept them for what they are. Although this is paramount to making progress it is easier said than done because it requires a level of vulnerability which most are uncomfortable with. Nevertheless, if we grant validity to the Buddha’s advice that the Dharma journey provides the opportunity to shape the evolution of humanity, it seems wise to confront the intricacies of our own blind spots sooner rather than later. Doing so could not only prevent years of developmental stagnation, but also help implement new levels of self-awareness that our world so desperately needs. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

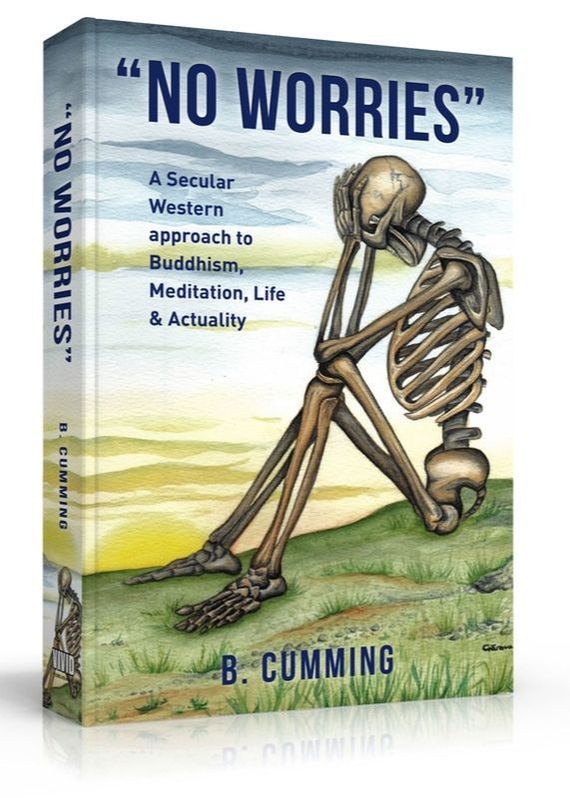

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |