|

Talking Dharma – Talking Encouragement

I am often asked to tell my own personal journey about what happened on June 13th 1980 and what happened after it. I have done that many times in the past and often drop bits of it in when I am communicating the Dharma. As far as the Dharma journey is concerned the period from 24th October 1954 to 13th June 1980 has very little relevance other than the entire period was the amalgamation of causes and conditions that brought me to the cliff’s edge with the decision to jump or not to jump. I often talk about my time within western Buddhism with the western Buddhist order that is now known as Triratna and have also talked a little bit about my origins within the Theravadin school, and the different Vajrayana schools of Tibetanism that I engaged with, but have rarely talked about the influence of Zen which was actually the major influence within a Dharma context. So, I’ve been reflecting on my time spent within the Zen school of Buddhism way back when and how very different that approach is in relation to the secular western approach that I now communicate. I don’t mean this to sound demeaning in any way, but it struck me that there would not be many people, if any, within the public at large who would last five minutes being subjected to the level of discipline required within Zen. Within that school there is hardly any social interaction. There are no coffee mornings, no sit around and chat nights. Even the weekly gathering for meditation is done in total silence. You arrive in silence, sit in silence, drink tea in silence and go home in silence. It’s rare even to actually sit around discussing the Dharma as a collective. You are given a teaching and then sent away to work on it and keep coming back to get clarification until you understand it fully. Finding that middle way balance between meeting the wants and needs of current day Dharma practitioners was always going to be difficult within a western culture that has developed very quickly into a meme society. But that does not mean it is OK to sit back and not review things once in a while to ensure we are not simply colluding with our habitual patterns of seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. The thing about the Zen tradition is that it is practically impossible to understand from a book, no matter how well that book is written. You can only understand it fully when you surrender yourself to it and embrace every aspect of its disciplines. According to the Zen tradition, it is only they who have communicated the essence of the Buddha’s awakening experience in an unbroken line from Master to student, from mind to mind, without making use of texts or verbal discourses that are of any authentic benefit. That is just the usual claims of the institutions of religious Buddhism that seem to have a need to do this kind of one-upmanship thing. In actuality, in both of the major schools of Zen, Rinzai and Soto there are great texts to explore and work through and there is an encouraged emphasis on study. But the most significant aspect of Zen is this term ‘surrender.’ In the Zen tradition the Zen Master uses any and all means at their disposal, confusing words, gestures, shouts, and even blows to enable the break through of those in training. He never allows the student to settle down into that comfort zone that is so appealing to many Dharma practitioners. In the Zen tradition we had this thing called the encouragement stick. Its traditional name is the kyosaku. I was subject to it for a number of years when in training and then, having been recognized as a Meditation Master myself, I actually got to wield it for a couple. In classical Zen there are numerous stories in which the Master makes judicious use of the stick to strike their students. In some of these stories, this treatment is said to bring on realization or breakthrough. More often though it simply indicates the Master’s rejection of the words spoken by his student who is recognised to be caught up in the distractions of delusion. The meaning of blows in classical Zen falls into two different categories. The first is that of ‘upaya’ the Mahayana concept of “skilful means’ which in my terminology would translate as a helpful act, as its motivational intent is the compassionate response of the Bodhisattva whose role it is to help you to awaken. The second category is probably even harder to accept outside of the tradition because it is about authority and let’s be honest we’re not that keen on perceived authority in the west. In this respect the stick was used to keep students in line with their undertaking to go for refuge to the three jewels and within that tradition, submit or surrender to their teacher. Now, here as always is the paradox. The teacher student relationship is about a two way development of trust. We are taught from day one to test and challenge everything we hear within the Dharma journey and that includes what our teacher tells us. But, within the Zen tradition the break through moment is said to happen when we surrender fully and it is at this point that trust is established and we no longer need to question anything. This is usually marked by being accepted into an Order. Nowadays, the stick has more or less become a symbol of authority. It is much the same way as the wearing of a robe or kesa is a similar recognised symbol that the wearer is either fully trained or in training and may be of help to others. What I can say about the use of the stick, bearing in mind I did get hit with it quite a lot in the early days, is that it never hurt physically and as far as I am aware I never caused any actual physical pain when I used it on others later. That, I hope, explains why it is called an encouragement stick. In Soto Zen you sit facing the wall but in Rinzai Zen you sit in the centre of the room, but the principle is basically the same. The student will raise their hand to ask to be struck. Usually this is when they have pain in the leg from sitting and the strike with the stick on the shoulders takes their attention away from it momentarily, or if they are experiencing drowsiness and need a reminder to pay attention. But even then there is something else going on. The student is also raising their hand to show the Master that they are being open and honest about their practice. They have developed a level of trust that knows that the Master is there to help them and know that hiding things from them or pretending is never going to do that. The other thing that can happen is that the Master notices a sitter nodding off, slumping or squirming from pain and taps them back into paying attention. How different this is with the relationship between teacher and student in the west. Quite often, any attempt to help the student to move forward will be met with the silent or unexpressed cry of “who do you think you are telling me what to do, you’re not so special,” or “but I don’t like that,” and all that kind of thing. There is nothing wrong with that. Let’s face it we’ve all been there at one time or another. But is it helpful to keep on repeating that same story to ourselves time and time again? Are we going to keep doing that until we find the perfect teacher? There is no such thing. The actuality is that you can become fixated on the biographies, the status, the recognition and all the other very appealing materialistic aspects of having your own private guru that you can show off to your friends, but the moment they tell you something that you don’t want to hear they will automatically become just another imperfect teacher. Why? It’s because you have not developed any degree of trust in them. So, when you find yourself reacting in this way, it is time to ask yourself a serious question: how many more years am I going to waste searching for the non-existent perfect teacher? I consider myself to have been fortunate to have met a Zen Master, who, despite being a westerner himself, was a traditionalist and refused point blank to collude with the emotional sensitivities of his western students. There is an old saying within Zen and that is “when the time is right for the student, the teacher will appear.” In my own circumstances I met my Master when I was sitting on a log in full police uniform, meditating in the woods at Nine Elms golf course in the UK. That is what I did most days at that time because I had been posted to a quiet little country village where nothing ever happened. I was literally a tax funded full time meditator. During our initial conversation it transpired that the centre where he taught was about ½ a mile away from the border of my own allocated beat in a place called Pratts Bottom, which for some reason still brings a smile to my face today. So, I went to see my boss and complained that there was not enough for me to do on my current beat and could I take over the adjacent beat which was vacant at the time. Two beats became one and now I could go to the centre every day for intensive one–on-one training and get paid for it at the same time. Bearing in mind the experience in 1980 preceded this, it didn’t take too long before the Master recognized that he could communicate with me on an entirely different level than all of his other students. This was seen by others as me being the teachers pet and that did cause some conflict within the community because some had been there for years and had an idea that length of service should count for something. In the Zen tradition there is a ceremony called Dharma transmission. It is an acknowledgement by the Master that the student is now the Master and they are the student. This is the mind to mind transmission I spoke of earlier. In effect, although the Master remains a Master he is indicating his choice of successor to ensure that the context he has set out remains intact for future generations. The date was set for my transmission ceremony and two weeks prior to that date my Master died of a heart attack. What followed was an implosion within the Order as people fought with each other for the power and prestige they believed the role would give them. They took sides and turned it into a political circus. I did not participate at all but observed. In all honesty I didn’t want the job but the pressure to take it on was immense. I chose an alternative approach and simply walked away as I did when my Theravadan teacher died. That Zen Order no longer exists today. When I first met Sangharkshita, the founder of Tritratna and we talked about my history and in particular my dead teachers he looked up and said “I suppose you’re going to ask me to be your teacher now?” I did and he is still alive and in his nineties and although no longer my teacher remains a friend and mentor. So, I hope you can see that it is not about the pedestal or the materialistic externals. Dharma communication is about deep friendship and two way trust. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

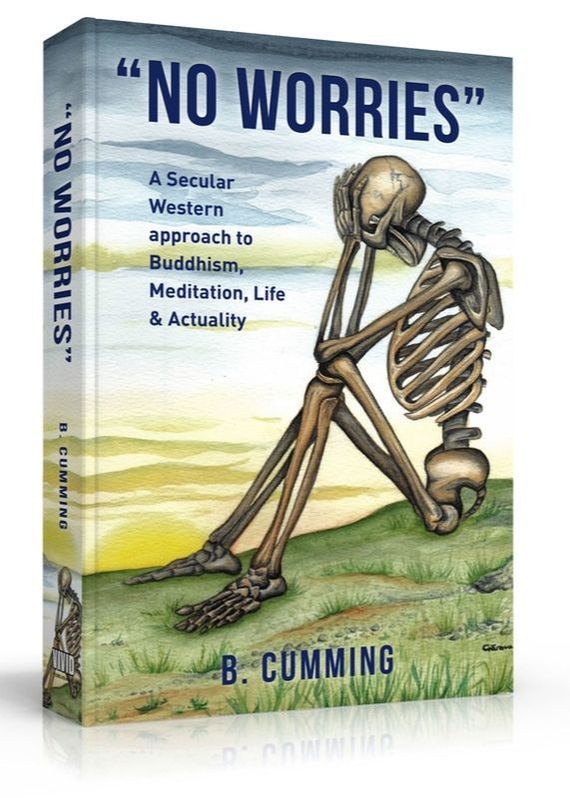

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |