|

Talking Dharma – Talking Stress

The experience of stress could be viewed as an assortment of unpleasant sensations, emotions and thoughts. We may experience it in many different ways such as pressure, anxiety, or even claustrophobia. It will be different for everybody because of the nature of our unique conditioning, but there are similarities that we can observe and learn from. Living within a modernised western culture, that is driven by performance, achievement and material worth, creates the conditions for on-going challenges that, at times, it can seem as though we are drowning in a sea of worries. At times we can become so overwhelmed by the experience it capsizes us and we go down like a sinking ship. The experience of stress can make us think we are cornered and that we have no way out. It can cause us to freeze, or it might stir up so much worry in the mind that it seems like we are choking to death. When stress is present within our experience there is no natural breath, no natural air to breathe. There is no open dimension. No is-ness. No creativity. When stress is present, what once might have seemed so simple becomes completely impossible and no matter which direction we turn there does not appear to be an escape route. With stress we become distressed. It is as though we are being pulled apart and are about to break. When stress is present, our physical body seems to get tighter, as if it is shrinking into itself. This releases chemicals that will create the experience of fight or flight, the fear factor of the pre-conditioned, biological, nature aspect of being. Psychologically, our thinking process gets fractured and runs riot and all awareness is lost. Even the slightest irritation or experience of not want, may set us off and we may lash out in anger. Or we might withdraw into ourselves, close off, and shut down to try and avoid the experience or try to divert it into something pleasant. In that moment we forget that we can just breathe into it with acceptance and allow it to move on of its own accord because in that moment we have attached ourselves to it as ours. Within our culture there is an endless list of things to be stressed out about. It could start with the basic necessities such as paying the rent or the mortgage or keeping or finding a job to do that. But even watching the news, reading a newspaper, or following the internet can quickly move those basic concerns towards global problems such as war, famine, environmental destruction or overpopulation and migration. We may even try to justify to ourselves that it is OK to do that because it makes us a more compassionate, loving or caring person. It is as if our worrying is some kind of badge of honour that is proof of our empathy, and sensitivity. When stress is present within our experience, we struggle to find someone or something to blame. We assume that there must be some external reason we are experiencing this and we believe that if we just remove that situation, we will be OK. If there is an obvious external cause, of course it may well be helpful to remove it. It may well be appropriate at times to stop seeing the person who we are blaming for driving us crazy. Time out may give us the opportunity to explore that belief and see through to its actuality. It may well be appropriate to stop putting ourselves in situations that we know sets us off. Again diversion in order to reflect is an appropriate thing to do. To divert without doing the introspection work just pushes around the cycle and we learn nothing from the opportunity. However, there are many situations we may not be able to do much about, no matter how stressful they may be. Throughout Buddhist texts there are numerous teaching that set out different aspects of the worrying mind that we are calling here stress. It is emphasised in them that is it helpful to make a commitment to do what we can to improve the conditions of life for ourselves, others and the world around us based on compassionate living. To enable this, we need to detach ourselves from the worrying mind in a process that unfolds the layers and layers of stress so that we can begin to unravel some of that attachment to it. A helpful starting point on this journey is taking a look at what drives our emotions, which is the entrenched and habitual patterns of thinking, speaking and acting. When we do, we will come to see that because of our distracted mind we create the conditions to make stressful situation worse. Because of confusion we change neither the situation nor our attitude but just add fuel to the fire. In classical Buddhism this is referred to as the endless cycle of pleasure and pain, or the eight worldly winds of hope and fear. Hope for happiness and fear of unhappiness; hope for fame and fear of insignificance; hope for praise and fear of blame; hope for gain and fear of loss. We spend our lives trying to hold on to some things that we like and get rid of other things that we don’t like in an endless and stressful struggle. A reasonable question to ask is what’s wrong with preferring happiness to unhappiness? Isn’t the pursuit of happiness what life is supposed to be all about? Isn’t it obvious that gain is better than loss? Of course there is nothing wrong with these ideas. But what the Buddha is asking you to explore is if it is helpful or not to move the mind away from worrying towards peace of mind. It is one thing to recognize what we would like to attract and what we would prefer to get rid of, but to use it as the basis of living a stress free life is not going to be helpful. The difficulty with the eight worldly winds is that they are opposites that keep us bouncing back and forth like a demented ping pong ball. We can’t have one without the other. When we are being blown around by the eight worldly winds the mind can only be in a state of worry because we are not content with the current experience as it is. If we are going to live life as some kind of sporting contest we will never hear the final bell or the final whistle. The first of these contests is happiness v unhappiness, pleasure v pain, worry v peace. We hope for happiness, but once we have it, fear arises, for we are afraid to lose it. Out of that fear we cling to pleasure so hard that the pleasure itself becomes a form of pain. And when worrying arises, no amount of wishful thinking makes it go away. The more we hope for it to be otherwise, the less peace there is. The second contest is fame v insignificance. We work hard to get to the top of our game. We are hungry for confirmation from others that there is nothing wrong with us and we are OK. We’re a nice person who they can love, respect and trust. And what happens when we don’t get it? Or even when we do and we know it is only the superficiality of the other person doing the same thing? We get the hump and blame them. When the penny eventually drops how hard we have to work to live in that world of superficiality of trying to be someone special, or different, our fear of insignificance is magnified. What actually lies behind our want for fame is revealed to be a worrying of inner desolation, shallowness or even hollowness. The third contest is praise v blame. We need to have our ego stroked constantly or we begin to have doubts about our self-worth or image. When we are not seeking to be praised for something we have said or done, we busy ourselves trying to cover up our mistakes so we don’t get caught out being something that we are not. But lets be honest here, there is never enough praise to satisfy us, and we are never free from the threat of being found lacking. Only if we are infallible, and nobody is, can we count on continual praise. So, although on the level of actuality we are always perfect as we are, the on-going struggle for the perfection of subjective reality will always end in tears of blame. The fourth contest is gain v loss. We invest in things and situations with high hopes of permanency and substantiality. That quality of hope is so seductive because we forget that no thing is permanent or substantial in and of itself. What goes up must come down. Just as we are about to congratulate ourselves on our success, the bubble is burst and the bottom falls out. Someone close to us dies or leaves us for a younger or richer model. We lose our job. Our house goes into negative equity. Inflation wipes out or entire life savings and fear once again rises to the surface in the form of stress. Our hope has fallen apart and we are afraid that things will keep going downhill forever. Over and over, things are hopeful one moment and the next they are not, and in either case the mind will not be at peace with itself, others or the world around it and will be worrying. These cycles of hope and fear that create the eight worldly winds occupy our minds and depletes our energy. No matter what is happening to us, we think it could be better, or at least different. No matter who we are, we think we could be better, or at least different. Nothing is ever good enough and therefore we can never be at peace. Should stress always be avoided? Can it be productive? Life within a modern western society is stressful. There is no doubt about that. It is suggested by many that contemporary life is the root cause of that stress and that we just need to accept that and get on with it as best as we can and turn to pills, potions, therapy and to the multi-billion dollar self-help spiritual woo woo placebo industry. But the Buddha provides an alternative to those things, that although for many may offer a sticking plaster of transitory comfort, offers a long-term solution. We have always had to make an effort to meet the pre-conscious drive to survive. We have always needed to feed ourselves to find shelter, and security. We have always needed to make an effort to meet the pre-conscious drive to replicate the species by finding a mate. The human world has never been the mythical Garden of Eden. The Buddha, in his primary communication of the four principal assignments sets out an alternative that does not deny or avoid that actuality of worrying. It points to ways in which it can be seen for what it is so you can do something effective to alleviate or eradicate it. The eight-fold journey that he proposes could be said to be the productive aspect of not trying to avoid stress and the end product is the realization of peace of mind within the realization of causality. The actuality of worrying and its cause is the single question that set the Buddha on his journey at the very beginning. No matter what direction you head in within his body of work and that of all other Dharma communicators that followed him you will end up at the source realization that it is the confused, conditioned, subjective self-biased mind that creates the stress because it wants any experience to be other than it is. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

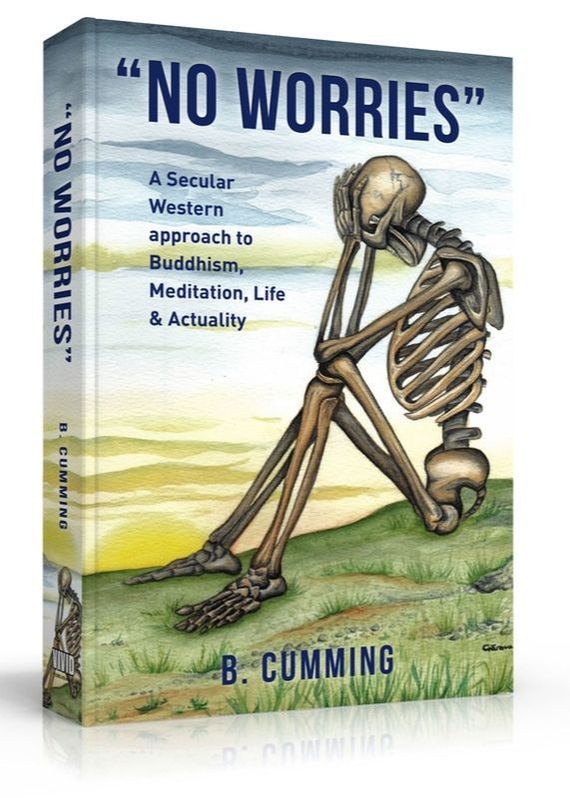

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |