|

Talking Dharma – Talking Angry Wisdom

Let’s begin with a couple of questions. Is anger an appropriate response to worrying or does it only cause more worry? Is it helpful or unhelpful? Can anger be harnessed into the wisdom of compassionate action? As we will hopefully come to see, the answers to these and other similar questions can be found in understanding what it was that the Buddha actually communicated, as opposed to what classical Buddhism promotes within its religious institutions. To begin this exploration we need to understand the distinction that the Dharma makes between anger and aggression. According to the Buddha aggression is an expression of the three poisons of want, not want and confusion that gives rise to the worrying mind. If we open our eyes with integrity into the way we live our own lives, how society is and even human history we will have to admit aggression is the greatest cause of the destruction of peace of mind and primary creator of worry. This is because, what defines aggression is the existence of the self-biased mind. Aggression is the energy of anger in the service of all that we define as “us.” Because of the pre-conscious drive to survive it is there ready to defend our sense of self and attack anyone and anything we perceive to be a threat. But, when anger is released from its service to the self-biased mind, it ceases to be aggression and simply becomes the energy of wisdom and compassion. Contrary to the marketing departments of classical Buddhism the awakening experience does not eradicate anger. It transforms it into compassionate action. It is totally possible, if not probable, that you can have an angry Buddha. It is just that the awakened mind is at peace with itself, others and the world around it because it is born of compassion. The anger of the awakened mind is the power to say no to worry. The angry Buddha is not angry with us, they are angry for us because they have been where we have been and know our experience and are driven by compassion to help alleviate it or eradicate it. That is what motivates the awakened mind to communicate the Dharma and nothing else. According to the ancient texts it is said that the Buddha’s compassion expresses itself through four types of energy. These are called helpful means. They are the four different ways that wisdom and compassion go into action to alleviate or eradicate worrying. First, the Buddha, in his imaged form or representation, can pacify us. It can help us to quench the flames of want, not want and confusion. The calm and pacifying Buddha image or representation is the one we’re most familiar with when we observe a Buddha image or statue at a Dharma centre centre or temple complex. Just observing such an image can find our worries often melting away and it is no coincidence that the Buddha figure has come to be recognised as a symbol of peace throughout the world and can be found now in domestic gardens of those who subscribe to theistic religion. Next is the energy of enrichment when we come into contact with the teachings of the Dharma, that wealth of resources that highlight our potential for awakening. The next is the energy of seduction where we are no longer alone but share our journey with others by way of mutual support. These first three energies align with going for refuge to the three jewels of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. The fourth energy is that of Bodhicitta, the arising of the will to realize awakening for the benefit of all beings. So, we can see within this teaching, in its pure, awakened form, when it is not driven by the self-biased mind, the energy of anger can be appropriate because it is born of compassion. This can often be hard for people to accept, but compassion is not always a fluffy pink bunny. There will be times, if compassion arises in its wisdom state which is outside of the influence of the self-biased mind, when compassion can seem harmful when you observe what is being said or done from the perspective of the ethical training principles. But often when that happens it is because we have possibly reverted to thinking they are black and white rules and regulations as opposed to being a way to observe and transform our mental state. When someone refuses to collude with our confusion we can take that very personal sometimes. In its pure, awakened form, when it is not driven by the self-biased mind, anger can be of benefit to us, others and the world around us. In our personal lives, it helps us be honest about our own infallibilities and also to have the courage to help others see how they are damaging themselves, but only when our motivational intent is authentically based in kindness, which of course is where the development of conscious awareness comes in so that we can be aware of our motivational intent. If it is not established it could so easily tip into unhelpful criticism. On a much larger scale, compassionate anger has been the energy that has inspired great movements for freedom and social justice, right back to day of the Buddha himself who taught against the prevailing religion of his day because of the way he recognized it moved people in the opposite direction from awakening and gave rise to the worried mind. So, the work in progress for the Dharma practitioner is to explore and find ways to work with the energy of anger so it doesn’t result in aggression, as well as exploring and finding ways to tap into its inherent wisdom aspect. There is a need to discover experientially where aggression arises from and how and why. That exploration primarily takes place within the practice of the four principle assignments, which of course is the eight-fold journey that incorporates both ethics and meditation. Within that it can be helpful to understand that although there are five basic ethical training principles, they are, in effect, all reflections of the overriding principle to seek to do the least amount of physical, emotional or psychological harm to ourselves, others and the world around us. Most human beings aren’t physically violent, but because of the self-biased mind and our conditioning, what we say and do can often contribute significantly in the emotional or psychological harm of others. The really sad part is that it’s usually the people we love or care about who experience this the most. We can also contribute to the harm within society when we collude, turn a blind eye or remain silent when we see or hear things that we know or even suspect are causing harm to others and that may even include having to be open and honest with ourselves about our own consumptive habits and choices. The overriding ethical principle applies to acts of body, speech, and mind. They are led primarily by the aspect of the principle that actively encourages you to live on the basis of kindness as a means of doing less harm by the observation of the quality of the state of mind in any moment. It helps us to choose how to think speak and act as an on-going learning opportunity in the development of human conscience. The Buddha set out a number of helpful meditation practices that are based in awareness so we are not swept away by the force of conflicting emotions like aggression. These practices allow us to take advantage of the brief gap in the mind between impulse and action. Through the practice of awareness, we become aware of impulses arising and allow a space in which we can consider whether and how we want to act. We move from the reactive mind of habitual patterns to allowing ourselves to respond as is appropriate to the experience. Without excusing, condoning or ignoring anything, it’s helpful to recognize that aggression is usually someone’s habitual reactions to their own worrying mind. There will be times when that will include us. So we need to be aware that caring for ourselves and cultivating kindness and compassion for ourselves first is not being selfish. It only becomes selfish when we cling to it without sharing it with others. As we have learned in the first principle assignment worry is inherent in the unawakened human condition. We are beings who worry and we don’t handle it too well. Often we try to ease our worry and only make it worse because we try to avoid it, divert it or deny it. The awareness of kindness practice as it develops gives us the confidence and space to experience our worrying without losing our stability or a need to blame others. Eventually, even when we are the targets of aggression ourselves, knowing it may come out of the other person’s conditioned, confused and worried mind helps us to respond in a more kindly and helpful way. Fear shame or guilt distorts the basic energy of anger and creates worrying. We fear that intense emotions like anger will overwhelm us and make us lose control. We’re ashamed that such unhelpful emotions are part of our makeup at all. And of course within our culture we have been conditioned to do guilt, give ourselves a hard time or beat ourselves up for not being perfect. As a result we protect ourselves against the energy of anger by either suppressing it or acting it out. Both are ways to avoid experiencing the full intensity of emotion. Both are harmful to ourselves and others. What we need is the courage to rest in the full intensity of the energy inside us without suppressing or releasing it. This the key to the approach to working with anger that was set out by the Buddha.. When we have the courage to remain present with our anger, we can look directly at it. We can experience its texture and understand its qualities. We can investigate and understand it. What we discover is that we are not actually threatened by this energy. We can separate the anger from the self-biased mind and the stories it creates. We can realize that anger’s basic energy is helpful, even enlightened. For in its essence, our anger is the same as the Buddha’s. When the energy of anger serves the self-biased mind it is aggression. When it serves to ease, alleviate or eradicate our worries and the worries of others it is wisdom. We have the freedom to choose which. We have the power to transform aggression into the wisdom of anger. The awakened energy of anger is the wisdom of clarity. It is sharp, accurate, and penetrating insight. It sees what is helpful and unhelpful, what is actuality and what is confusion. The good news is that the confused and misdirected aggression that causes worrying is just transitory and insubstantial. Now we just need to realize that. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

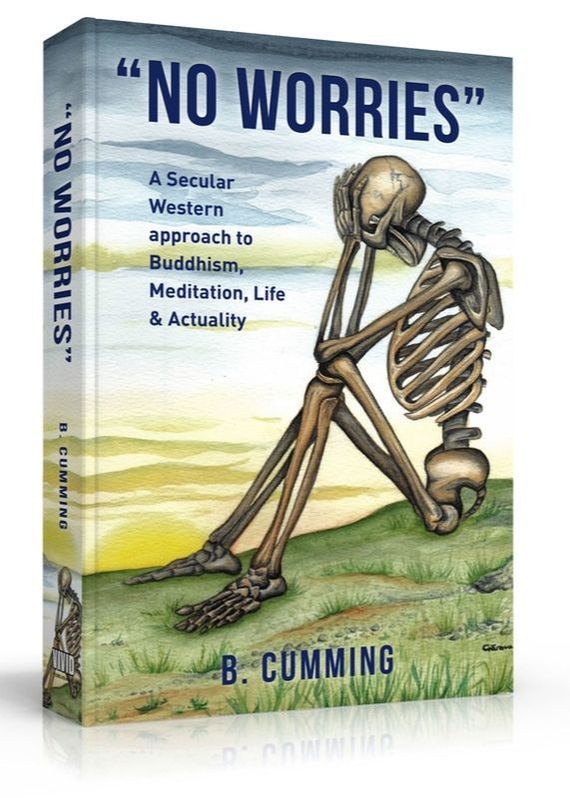

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |