|

Talking Dharma – Talking Responsibility

The world we experience is filtered through our senses, our memories and our conditioning. For many the world is a cruel, heartless and dangerous place. For others it is an amazing place that is beautiful, compassionate and joyous. The actuality is that it is both of these things and more. To deny that there are dangers in the world would be silly. To deny that there is no compassion in the world is equally silly. What the Buddha suggests, within his communication, is that we develop conscious awareness, the paying full attention to our thoughts, words and actions and taking 100% responsibility for them. In classical Buddhism this is called heedfulness. In secular western Buddhism we call this responsibility. From the moment we are born into this world there are only three inevitable things that are going to happen to each of us. This mind/body process that we think of as us is going to age, get sick and die. Now, we can either pretend that is not going to happen, try and divert our attention away from it, or totally deny it. But if we do it will only cause us to worry. The moment we accept that inevitability fully, we actually allow ourselves the opportunity to start taking responsibility for ourselves and start living authentically in each moment. It is really helpful to remain aware of these inevitabilities so we can come to realize that they are not dangers but just a normal part of what it means to live as a human being. As we make our way through this life we will encounter endless experiences that may trigger sickness or death. Without an on-going awareness of their inevitabilities can we really say that we are taking responsibility for ourselves? Reflecting on these three actualities prepares us to take responsibility for what we think say and do. Otherwise, we tend to lose sight of them and our responsibility level drops and our guard gets let down into an unrealistic comfort blanket and an illusion of safety. Then, when that safety is suddenly challenged by a direct experience, we end up in fear and worry ourselves to death, literally in some cases. This is not being responsible for ourselves, others and the world around us. Quite often, in the ancient texts, we find the Buddha communicating that the basis of all our helpful qualities is responsibility. Not inherent goodness or compassion, but responsibility. He urges us to pay attention to the actuality that there are internal and external dangers and that our thoughts, speech and actions will make the difference between worrying and peace of mind. This is why he urges us to take responsibility now and not keep putting it off to some indeterminate time in the future. After all, it is not inevitable that you will actually have a future if you do not take responsibility now. It is by taking responsibility for what we think say and do, that we can develop generosity, insight and kindness. He points out that we are not inherently generous or kind because our minds are so quick to change that we’re not inherently anything, good or bad, aside from being aware. If we’re taking responsibility, we’re kind not only when others are kind to us. We’re kind because we see that kindness is the most helpful course of action, even in the face of the unkindness of others. This could be why the Buddha told his followers, when they were ready, to go out into the forests to face some of the dangers there, so that they could overcome their complacency and begin to take responsibility in regard to the threats to their physical, emotional and psychological well-being. That way they could learn to bring out their most helpful qualities even when, especially when, confronted with the worst that the forest had to offer. In many of the ancient texts you will find stories of his followers living in solitude in the forest and discovering that in the face of hunger, sickness and dangers from wild animals, that the most helpful way to keep their minds free from worry was to take responsibility and reaffirm their commitment to go for refuge to the three jewels. Note I said when they were ready. The Buddha never forced his followers into the forest. Like a loving father who provides safety for his children during their early years, he gradually encouraged them to begin taking responsibility for themselves until he was assured that he had provided them with all the skills they needed and were ready to let go of his shirt tails and face the challenges of those inevitabilities on their own. Safety, danger and responsibility are popular themes throughout the ancient Buddhist texts. The Buddha repeats these themes often, not only to his followers, but also to members of the public who come to hear him speak. He urges them time and time again to reflect on the actuality of the three inevitabilities and to consider what would be the most appropriate way to find safety and avoid danger. Needless to say, that his solution was taking responsibility in the form of going for refuge to the three jewels and engaging fully with the eightfold journey with integrity. So, let’s take a brief look at some of the Buddha’s communications about safety, danger and taking responsibility. According to the Buddha, safety is only assured within the awakening experience. Until that has been realized you have to accept the actuality that you will need to let go of some things that are unhelpful and only retain those things that are helpful. The world of the conditioned self-biased mind is a series of trade-offs and it is only with the development of insight that you can work out what the wise trade is. If you lose sight of this actuality you may well find yourself walking the Dharma journey in a complacent bubble of what you assume to be a responsibility free zone where you can have your cake and clarity. So he advises that people who live in complacent bubbles are the ones most likely to thrash around wildly, endangering themselves and others, when that bubble bursts. According to the Buddha, the most long lasting aspect of what you think of as you is your actions in this life. The mind/body complex is yours only until your brain stops working. All of those close to you, like family and friends, at best, are yours no longer than that. The results of your thoughts, speech and actions will carry on well past your death. That is why he suggests that we need to take responsibility for them now to ensure that the effects we have created are of help to others now and the world we leave behind. Specifically, he points out a set of five basic ethical training principles that he suggests will help you to take responsibility for the quality of your own mind state and how it affects you, others and the world around you and possibly be an inspiration to others in adopting the same set of principles within their own lives. To experience a sense of safety in the world, the Buddha says you first have to provide safety to the entire world. He says that you do that when you live the eightfold journey and practice the five training principles with integrity, because when you take on such a responsibility you can do no intentional harm to yourself, others or the world around you. In return, you get not to have a worrying mind but can be at peace. If, however, you follow the training principles only half-heartedly, or with a lack of awareness like some kind of auto-pilot rule bound robot, or begin to use rationalization and justification to find excuses, it’ll be as effective as building a fence around your house but forgetting to hang the door in its frame. You leave the gap for worrying to enter and steal all your tools. What are those tools? Without any doubt meditation is the greatest tool in our kit. In particular the awareness of kindness and its later explorations into compassion, empathetic joy and equanimity provide the perfect opportunity to affect our thoughts, speech and actions in a way that they are going to be of help to us, others and the world around us. Combined with the awareness of the breath we can develop ways to let go of worrying in the present moment and find that neutral balance of contentment between the experiences of pleasure and pain, like and dislike, want and not want. According to the Buddha, when the mind is trained in this way, it’s like a vast lake of clean water. You can throw a lump of salt into the lake and yet still drink the water, because it’s so vast and clear. Otherwise, your mind will be like a small cup of water. The same lump of salt thrown into the cup will make the water unfit to drink. One of the areas the Buddha often talks about is the benefit of being around like-minded individuals. He suggests that hanging around too often with those who do not share our core values can be unhelpful because there is a natural tendency to be influenced by the need to be loved, liked or well thought of that is central to group think and behaviour. The danger here is not so much what others may do to you, but in what they can influence you to do. Their responsibility is theirs, even if they are unaware of it and you are responsible for you and have chosen to be aware of it. Even when you’re mistreated by others, their responsibility doesn’t become yours unless you react in an unhelpful way or reciprocate their action. Often it can be the closest people to you, your family and best friends who have the greatest influence and in this respect it presents the most significant danger. This means, that you have to train yourself not to fall for the rationalizations and justifications, or to be tempted by the rewards that some people will offer you to let go of your responsibility to develop and maintain peace of mind. One of the difficulties we have is that we live in a world of communication and the use of words can be the thing that causes us to react and therefore cause us to worry. So, it is helpful to learn to distinguish between speech that is genuinely harmful and speech that is only harmful at a surface level. Unpleasant or unhelpful words that are intended to get you upset are harmful only on the surface. Unpleasant or unhelpful words that sink deep into your subconscious as some kind of on-going pattern are the ones that can cause long-lasting harm. By training the mind to become less reactive and more responsive it is helpful within that process to depersonalize the words. There are two basic techniques that you might find helpful. The first is to remember that human speech all over the world has always been, and always will either be kind or unkind, helpful or unhelpful, accurate or inaccurate. The actuality that someone may be saying unkind, unhelpful or inaccurate things to you right now is nothing out of the ordinary so there’s no reason to think that you’re being singled out for any special mistreatment. Understanding this means you can let go a bit and take it more in your stride. Secondly, you can tell yourself when something unhelpful is being said, “It’s just a sound making contact with the ear. It too will pass.” And just let it be that. There is no need to build any internal narratives around that, which means you do not have to react in a way that will cause you to worry. Let’s face it, you have two ears, so you’re bound to hear both pleasant and unpleasant sounds. But you can also develop discernment around how you use your ears and relate to those sounds. If you can let the words stop at the contact, they won’t present any danger and you are taking responsibility to ensure that happens. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

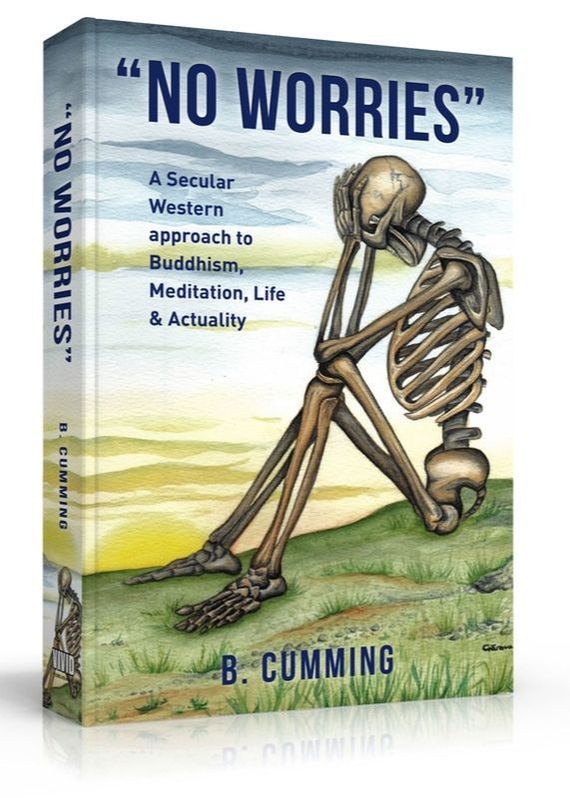

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |