|

Talking Dharma – Talking Equanimity  Equanimity is the foundation of wisdom and is expressed as compassion. Superficially, it is experienced as a dry neutrality, or a cool aloofness, but it's actuality produces a radiance and warmth of being. Contrary to the criticisms of those who do not know this experience, it is not about indifference, coldness, a lack of emotion, boredom or hesitation. Equanimity is an expression of calmness and contentment with the way things are, as they are, in any moment of existence. The Buddha describes equanimity in the ancient texts as the abundant mind, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility and without ill-will. Equanimity is the ability to see without being caught by what we see which results in peace of mind and in Pali is known as upekkha which translates as to look over, in terms of seeing things as they are and not how we believe them to be. Equanimity can also refer to the ease that comes from seeing the bigger picture, to see with patience, to see with understanding. For example, when we know not to take words spoken against us personally, we are less likely to react to what was said. Instead, we remain at ease or within equanimity. Another aspect of equanimity is represented by the Pali word tatramajjhattata. Tatra, means there. Majjha means middle, and tata means to stand or to pose. Put together, the word becomes to stand in the middle of all this. Equanimity, therefore means being in the middle and refers to balance, to remaining centered in the middle of whatever is happening. This balance comes from inner strength or stability. The strong presence of inner calm, well-being, confidence, vitality, or integrity can keep us upright, like a ballast keeps a ship upright in strong winds. As inner strength develops, equanimity follows. The experience of equanimity could be compared to the love that a grandparent has for their grandchild. It is very different from the relationship they had with their own children. Having gained some wisdom in the field of parenting they tend not to get caught up in the drams of their grandchildren’s lives so easily as they did with their own children. The love is there but the attachment to the drama isn’t. The development of equanimity is said to be the perfect protection from the eight worldly winds: praise and blame, success and failure, pleasure and pain, fame and disrepute. Becoming attached to or excessively elated with success, praise, fame or pleasure sets up the conditions for worrying to arise when the winds of life change direction. Success on any level is great and there is nothing wrong with that, but it can easily lead to arrogance which possibly sets up us to not be successful in future challenges and that will cause us to worry. Becoming personally attached to a need for praise can give rise to conceit and the energy we need to use to maintain that conceit drains us physically, emotionally and psychologically. Identifying ourselves with failure, we may experience a sense of incompetence or inadequacy. Reacting to physical pain, we may become discouraged. If we understand, realize or experience that our sense of inner well-being is independent of the eight winds, we are more likely to remain contented or the mind will be at peace with itself, others and the world around it. A helpful approach to developing equanimity is to cultivate the qualities of mind that support it. According to the Buddha there are seven different ways we can do this. The first is the development of integrity by adopting a set of ethical principles that are not rule bound. When we live and act within integrity, we experience confidence about our thoughts, speech and actions because we have learned to take responsibility for them without recourse to blaming anyone else or any external event. There can be no blame within the experience of equanimity.

The second support for the development of equanimity is learning to trust in going for refuge to the three jewels and in particular trust in the context in which we have chosen to do that. Shraddha is often translated as faith within Buddhism, but this can be problematic in the west because of our conditioned association with that word. Faith can lead to blindness, but trust is built on our direct experience of the helpful developments of our practice of transformation as we walk the Dharma journey. The third support is the development of calm, kindly awareness through the concentrative process of formal meditation practice and in our everyday lives outside of formal sitting. Just as we would go to the gym to develop physical strength, balance, and stability of the body, there is also a need to do those things by exercising the mind and this includes spending time with like-minded individual, studying the Dharma, discussing and practicing together. All of these things are geared to eradicate our worries and when they are we are less likely to be blown about by the worldly winds. The fourth support is the development of a sense overall well-being. We can’t just sit there and hope that things will be OK. We actually need to do things to take care of ourselves. Quite often within western culture, because we have been conditioned to think that we need to put others first we forget to consider how much harm we are doping to ourselves in the process. It is crucial to understand that from a Dharma perspective taking care of yourself, being kind to yourself is the most unselfish thing you can do. You really are not much use to others until such time as you are in a helpful space yourself. The key to understanding this is recognising the difference between a human being and a human doing. Even taking time out to enjoy a cup of tea or watch the sun go down can be a part of awareness training. The fifth support for equanimity is the development of insight. Insight is a crucial factor in the realization of conscious awareness. To be in conscious awareness is to have an accepting awareness, to be present to whatever is happening without the mind resisting. Insight shows us how to separate people’s actions from who they are. We can agree or disagree with their actions, but remain neutral in our relationship with them. We can also understand that our own habitual patterns of thinking, speaking and acting are the result of impersonal conditions. By not taking them so personally, we are more likely to stay at ease with their arising. Another way insight supports equanimity is in understanding that people are responsible for their own decisions, which helps us to find equanimity in the face of the worrying of others. We can wish the best for them, but we can also avoid getting caught up in their dramas. One of the most powerful ways to use insight to facilitate equanimity is to be aware of when equanimity is absent. Honest awareness of what makes us imbalanced helps us to learn how to find balance. The sixth support is irreversible insight, a deeply transformative seeing into the nature of things as they are and one from which there is no return. Here we are talking about the two major insights of impermanence and insubstantiality, the continuity and no-thing-ness aspects of causality. When realized we see that things change so quickly that we can’t hold onto anything, and eventually the mind lets go of clinging. Letting go gives rise to equanimity. The final support is freedom. This arises when we begin to let go of our reactive tendencies and move into responding as is appropriate to each experience as it is. We begin to notice how there is less worry in the mind and we find ourselves more contented in our daily lives. For example, if you think back to the kind of things that cause worries when you were much younger, let’s say the dreaded teenage years for instance, those kinds of worries don’t happen now. OK, they may have been replaced by different ones, but the point is we became unattached to them and let them go. The Dharma journey is about expanding the range of life experiences in which we can develop ways of letting go. It is about integrating external observation and internal introspection into conscious awareness that result in alleviating or eradicating our worries so that they can be replaced with contentment or peace of mind. Equanimity is, according to the Buddha, the experience of the awakened mind. It does not contain any aspect of worrying that can be found in both pleasant and unpleasant experiences. It is way beyond what we understand to be happiness, delight or joy. The experience of equanimity is undisturbed by the ever changing circumstances of life. This thing we call mind remains at peace as events change from hot to cold, from sweet to sour, from easy to difficult. It could be said to be the neutrality of the Buddha’s middle way approach but that neutrality can be ever so subtle to discern because of the existence of the conditioned self-biased mind. The actuality of equanimity remains steady throughout all experiences. Although there is still the awareness present that the mind has a tendency to be drawn towards the pleasant and to move away from the unpleasant, as it has no attachment to a need to act upon those things it therefore remains at peace with itself and simply responds as is appropriate to the experience. What is missing from the experience of equanimity is the personal preference aspect that would normally dictate what action should be taken based on one’s conditioning factors. Equanimity is the willingness to be open to all experience, as it is, with no separation between pleasant and unpleasant in order that peace of mind can be established and maintained as the central and defining balance of life in which you are no longer pushed this way and that by the coercive distractions of want and not want. Equanimity has the capacity to experience and accept extremes without the drama of worrying rising to the surface and throwing you off balance. It takes an interest in whatever is happening simply because it is happening. The authentic Dharma practitioner thrives on unpredictability. They test and refine inner qualities. Every situation becomes an opportunity to abandon judgment and opinions and to simply pay full attention to what is actually happening. Situations that would normally be considered a least inconvenient become a fertile ground for practice where they can learn how gracefully they can compromise in a negotiation, how the mind can remain at peace when you have just driven round the car park three times looing for a space and manifestation of one hasn’t yet happened. It’s when that six hour delay for your flight becomes an opportunity for meditative reflection rather than worry. All of life’s inconveniences can become opportunities for the development of equanimity. Rather than shifting the blame onto an institution, system, or person, one can simply choose to be at peace within the experience of inconvenience. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

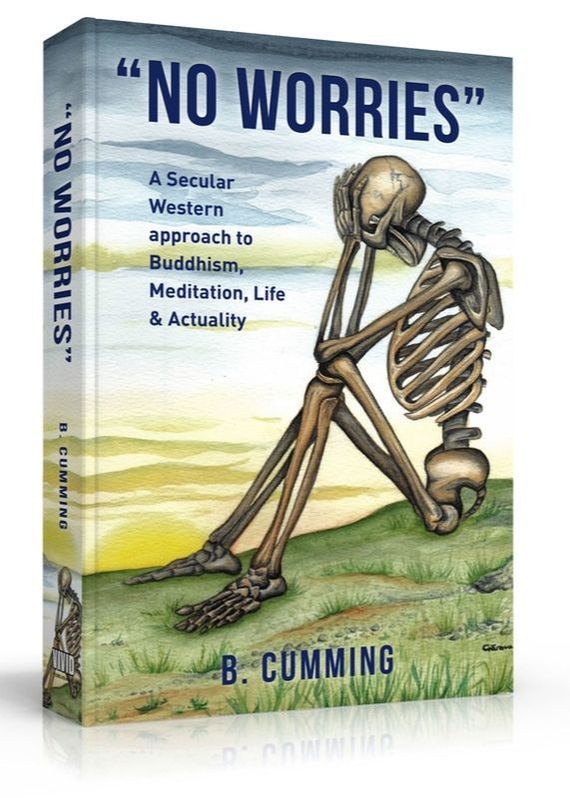

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |