|

Talking Dharma – Talking Practical Kindness  The first principal assignment the Buddha sets out is that we have to understand fully what worrying is, what its nature is and to realize how it is an inevitable part of what it means to be conditioned by the self-biased mind of being human. Although an integral part of that journey is all about us, it isn’t until we can recognise and empathise with the worrying of others that real progress can be made. In the traditional story of the life of the Buddha there is an example of this from an early childhood memory when he witnessed his father taking part in the annual first ploughing and sewing of the crops. As he watched the plough cut through the earth, he became aware of how much life was disrupted and destroyed in the simple act of planting food. He noticed the field mice hurrying away, the bugs running for cover and the worms being sliced in half. As he sat under the shade of a tree contemplating what he had seen, his first experience of meditative insight arose, although at the time, it is said, that he was unaware of what it was that had happened. The insight was that no matter what we do, or how we live, to survive on this earth we cannot avoid doing harm. He realized that in seeing the worrying of others it quite naturally causes us to worry. Even if we stopped eating meat and became radicalized vegans, or fruitarians, or brush the path that we walk on, or wear a face mask like the Jains, it is impossible to live on this planet as a human being without causing some degree of harm. It is suggested within classical Buddhism that this memory from childhood was the seed which later ripened at the age of 29 that set him off on his journey to find an answer as to the cause of worry and to see if it could be eradicated. When we begin to open ourselves up to the experiences of others, we do so because we know what it is to worry ourselves and how painful that can be. Because of this, empathetic kindness arises as a natural response. The biggest problem is that within the pre-conscious, biological, nature aspect of being there is an inherent drive to avoid pain, so we tend to pretend that it isn’t happening. We suppress it and put a brave smile on our faces and when we do that, we store up harm for ourselves, others and the world around us for some possible future moment. By trying to shield ourselves from the emotional and psychological pain of worry in the present moment by rejecting it, we also avoid facing the pain we see all around us. By distracting ourselves from it, or avoiding its actuality or trying to distance ourselves from it, in effect, we distance ourselves from one another. We lose the interconnectedness that makes kindness possible. The most helpful way there is to maintain that connection is to extend our awareness to include all of our experience, not just the parts that we are comfortable with. Meditation practice is a helpful way to work through that process of becoming aware of whatever arises in our thought process. In meditation we are learning to be open to who we are, and whatever our experience is with an acceptance of it in each moment. So meditation practice is not just about learning to concentrate, it is also a way of being kind to ourselves. It is a process of integration. By learning to accept ourselves and our experiences in meditation, we are, at the same time learning to accept other people. This is more than just putting up with people. It is about understanding that they are no different than you when it comes to the experience of worry. This acceptance is the tender and gentle process of opening ourselves to the actuality of interconnectedness, that common ground of worrying. Kindness really only begins at this immediate, personal level of experience. By developing an attitude of acceptance and fundamental friendliness, we can lessen not only our own fear and worry, but also that of the people around us. We can actually shift the atmosphere in the direction of friendliness and kindness, and in that way be of benefit to ourselves, others and the world around us. When we do this others notice, there is an inspiration opportunity here. A little seed of our own is planted and provides an opportunity for the growth of another. There is a really helpful meditative exercise that can be done with a partner that explores what this is all about. You begin by sitting facing each other. Take your time to let any giggles to stop and just settle down and sit with the breath for a while. This can be quite confronting at first, even if it is with a close partner but stick with it. When you’re ready begin to include your partner in the practice. As you breathe out, extend your attention out to them and as you breathe in consciously include them into your awareness. Avoid doing any analysing and just be fully aware of their presence. Pay attention to the space between you and your partner and your connection to each other. Bring into that mutual space, as you breathe out, a quality of acceptance and simple friendship to your partner. On the in breath, take in and receive the acceptance and friendship that your partner is extending to you. Experience the acceptance and friendship circulate between the two of you. To conclude, spend a few minutes simply sitting together quietly. When we sit quietly like this with another person, we gradually become more aware of that person’s presence. We begin to accept and appreciate them. Those two qualities, awareness and acceptance, are the foundations of the development of kindness. The difficulty is that we tend to keep getting absorbed with ourselves, and losing our awareness of others. When we are caught up in our own concerns, our appreciation and awareness of others falls away. You might think that is can be helpful to ignore our tendency to focus on our own concerns and ignore the concerns of others, but in the long-term, if you want to develop kindness, we first need to understand our own selfishness. That is where we begin. We need to stop and take a good look at this fixation with ourselves so we can move towards selflessness.

Being selfish is so habitual that most of the time we are unaware that we are doing it. Don’t give yourself too hard a time over this. The inherent drive for survival within the pre-conscious aspect of being creates this self-interest that is like a background noise we no longer hear. It’s like there is a constant buzzing that we cannot seem to shut off. There is this auto-pilot self talk going on that is saying “What’s in it for me, what’s in it for me?” Let’s not kid ourselves here. It happens if you are a thief or a nurse. It’s easier to spot in children. If you ask a child to cut two pieces of cake, one for them and one for a sibling, it is likely that their piece will be a little bigger, or if not bigger, it will have the bit with the icing flower on it. A shrewd and observant parent would get one child to cut the cake and then the other to choose first. Voila! Two identical slices. We learn all about sharing as kids but by the time we have grown up we have also learned how not to be so blatant with our selfishness. It’s still there. We’re just sneakier about it. When we are in the greatest pain, it can be really difficult to stretch beyond our own concerns. One of my favourite stories within classical Buddhism is when the Buddha meets a grieving woman carrying the body of her only child. She was completely overcome by grief. In recent months she had lost everything, her parents, her husband and now she had lost her only son. She refused to allow the body to be taken away for burial because she was in complete denial that he was dead. She begged the Buddha for a cure. The Buddha agreed, on condition that she brought him a single mustard seed from the home of any family in the nearby village that had never experienced death. The women began her quest, but as she went from house to house, she did not find a single one that did not have a story about grief and loss through the death of a loved one. In her search for the mustard seed, she was gradually drawn out of the preoccupation with her own pain as she realized the level of pain all around her. When she arrived back to where the Buddha was she was ready to let go and bury her child. There is a meditation practice called shared awareness that works to eradicate this tendency towards selfishness. It is a practice specifically designed to undermine and remove the barriers that stand in the way of our natural impulse towards kindness. In time it moves from putting ourselves first, then viewing ourselves and others equally and then finally putting others before ourselves. Our habitual activity is to protect ourselves by constantly picking and choosing what we like and rejecting what we don’t like, but here we work to reverse that. Instead of taking in what we want and rejecting what we do not want, we take in what we don’t want and send out what we do want. It might sound a little crazy at first but it aims to reveal to us the actuality that when we see all others in pain, we are included in that experience because of interconnectedness. This practice is complimentary to the awareness of kindness practice and is a natural extension of it. I suggest it is not helpful to engage with it too soon, but it is helpful once you are fairly established in kindness for self. If you are still struggling in the first stage of the awareness of kindness practice this is not going to be of benefit to you just yet. There are four stages to the practice. The first stage is preparation. It’s about taking some time to settle in with the breath. In the second stage you begin to explore emotions. Each time you breathe in, using your imagination, you breathe in the pain and worrying of others. You allow that pain to be transformed by the kindness you have for yourself and each time you breathe out, you breathe out that kindness back towards those who were worrying. Here you are taking the habit of grasping and rejecting and you are reversing it. You begin my staying close to home with somebody or something that actually affects you personally. In the fourth stage you expand the practice beyond your own immediate emotional experiences and focus on all beings in all directions. It is quite a strong practice and not for the feint hearted and shouldn’t be played round with. At times it may seem threatening, but that is the point in some respect. It threatens our sense of self and recognises the actuality of interconnectedness. This practice is about making a genuine connection with ourselves and others. It is a practice that draws us out beyond our own concerns to an appreciation that no matter what we happen to be going through, others too have gone through experiences just as intense. It is the starting point for authentic empathy. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

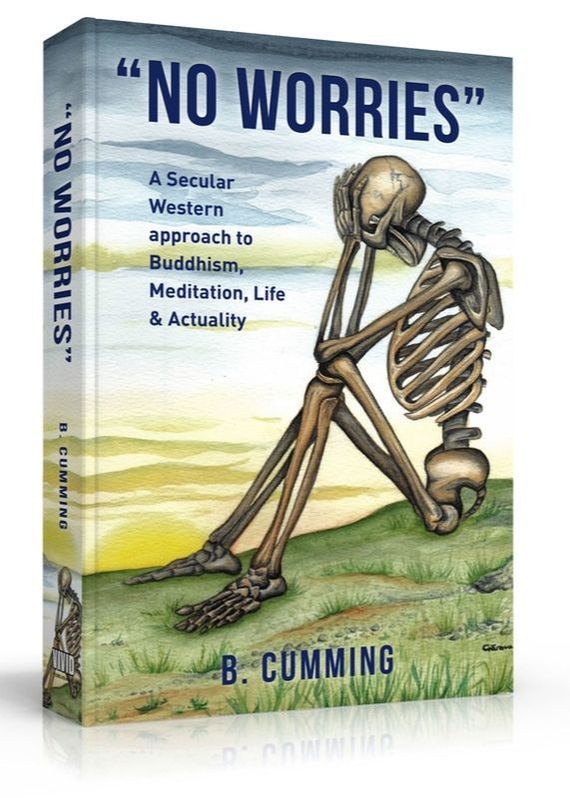

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |