|

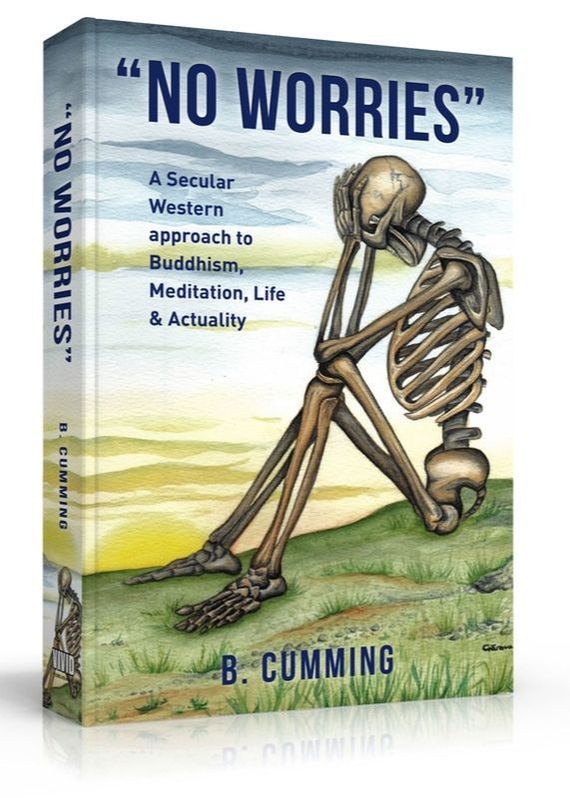

At some point in the future, if a scholar or historian could provide evidence to suggest that no such character as Siddhartha Gautama ever actually existed, it would not make one bit of difference to the validity of the Dharma. It has never been and never will be about the communicator. It has always been about the communication. There is a well known image within Buddhism that is replicated on the back cover of the book “No Worries” which highlights this. It is a picture of a finger pointing at the moon. The moon represents actuality and the finger represents the awakened mind pointing towards it. But, a historically updated version of the traditionally handed down life story of the historical Buddha is still of great relevance to us. The story itself is full of symbolism and inspiration that can help us to understand why his original communication is as relevant for us in modernity as it was back in India 2,600 years ago.

The single most important point about the story is that Siddhartha began his life as an ordinary human-being the same as you and I. There was no divine intervention. There were no pre-ordained special circumstances. He arrived on this earth simply as a result of the human birth process that resulted from his parents having sex. We have been told his birth in Lumbini was a complicated one and led to the death of his mother a few days later. His father was the head of a regional clan and would have been a relatively wealthy man and the young Siddhartha, would have wanted for nothing. Here is our second significant connection with the story. No matter what our personal or financial circumstances, materialistically speaking, we are far better off now than the young Siddhartha would ever have been. Just as Siddhartha would have been educated within the culture, traditions and beliefs of his time, so were we in ours. He would have been conditioned by his surrounding influences just as we have been. In so many different respects, his early life would have matched most of ours with personal relationships, job, family, social network and the on-going pursuit of things he liked that gave him pleasure and the avoidance of things he didn’t like. This is what the symbolism of the story is all about. If he could break free from his worries, there is no reason why we can’t. By the age of 29, he was happily married with a young son whom he adored and had every available pleasure available to him. Yet life began to raise big questions for the relatively young Siddhartha. It began when he noticed that he couldn’t find lasting satisfaction with anything. Much of his life was very pleasurable but he noticed that pleasure could not be sustained. When pleasure ended, he would find himself sad, bored or restless again. He began to reason that there must be more to life than his current experience. He began to dwell on such things as the meaning of life and questioned whether it just meant that you are born, age, get sick and die, and throughout that process you go round in circles of pleasure and pain. These ideas appear to have weighed very heavily on him and caused an ever increasing sense of worry about the direction of his life. If we reflect on this for a while, once again, we will see how connected we are to this part of the story. This kind of questioning arises in many different ways for different people and can act as a trigger for change. Someone close to us might have died. We might have lost our job. Our relationship with a partner might have come to an end or we have reached some other kind of crisis in our lives that makes us stop and take a look at the bigger picture. Or, for some, it just might be that niggling feeling of background angst that we can’t seem to find the reason for and that is preventing us from experiencing contentment. There is that underlying sense of incompleteness that we need to have something, do something, or be something to be whole. However people arrive at this moment it can be crunch time. For some it will be the trigger for a change in direction and for others it will be a missed opportunity. They will try to suppress the experience, ignore it, hide from it or justify their situation. They continue to go round in the same habitual cycles of pleasure and pain because in the background there is some kind of fear of change. For many it is clear that there is a comfort blanket effect in clinging to what we think we know, even if it hurts us, rather than be prepared to step outside of that comfort zone and embrace the opportunity and actuality of change. It certainly was a crunch moment for Siddhartha as he concluded that the only option for him was to leave his comfort zone and go off in search of an answer to why he worried and if it could be ended. For many, the thought of leaving our family, friends, job or our home would be the last thing we would do and there are those that think that what Siddhartha did was a bit of a cop out or showed a lack of responsibility, but this was quite the norm in India during this period. It is clear that both his son and his wife were well taken care of during his absence and they were all reunited later. Fortunately for us, because of his decision to go in search of an answer to the worrying that he was experiencing, we do not have to do so. He did all the hard work for us, and as a result we now have a practical method that can be applied to arrive at the same conclusions, without the need to put ourselves through everything that he did. Nevertheless, it probably won’t be easy. We live in a very different world and have very different things to overcome but essentially, what he communicated is that we too can reach this state of clarity by our own efforts in whatever life circumstances we find ourselves. Having left his home he spent the next six years living as a wandering beggar. During this time he met and aligned himself with all of the apparent spiritual teachers he came across during his travels. We are told that he was an ardent student who tested and challenged everything he was taught to the max and was often invited to join various communities as an equal to the teacher. But, he always declined because he found that despite being of great benefit, none of these teachers seemed to have the answer he was looking for. With each method, technique or teaching, he found that even when he pursued it fully with 100% integrity it always fell short in some way or other. Having done the rounds and tried out everything that was on offer, he turned to taking up extreme austere practices, such as almost starving himself to death or subjecting himself to extreme physical pain. Back then and even today in some parts of India you will you find the most bizarre practices being carried out by those who are on some kind of spiritual quest. When we reflect on this part of the story, perhaps we can recognise something of ourselves in it. How many of us have dabbled in a never ending range of activities that promised us the happiness we sought? What fortunes have we spent on self-help books or the latest book or DVD by our celebrity guru? How many times have we been apparently healed by crystals, reiki, gongs, mantra’s or prayers only to find we are very quickly back at square one? How many different meditation methods have we tried and decided that they didn’t work after a couple of sessions? How many apparent teachers have we found and dismissed because they did not match our expectations, or projections, or as is usually the case, because we didn’t like them? Do we try anything or anyone new that comes onto the scene or the market? We really do need to be honest with ourselves about this because this kind of thing is exactly what Siddhartha was doing for six years and got nowhere. There is a massive message within this part of the story for us if we take a good look at it and learn to laugh at ourselves about it. We now come to the second major turning point for Siddhartha. This, I suggest, was his first insightful experience. Having experienced and exhausted two extremes of behaviour namely living a full-on hedonistic life of pleasure and the other extreme of austerity, he came to the conclusion that neither extreme was the answer. He concluded therefore that there must be a middle way and it was this insight that moved him to give up extremes in favour of the simplicity of finding a middle way. This middle way philosophy is a theme that runs through almost everything he ever communicated. During the six year wandering period, he learned and excelled at taking up a range of meditation practices but none of them had taken him all the way. It was, as he sat under the shade of a large fig tree in a place called Bodh Gaya that he remembered when, as a child, he watched his father ploughing a field and how when he placed his full attention on the slow and gentle movements, his distracted thought patterns subsided and he became very centred and concentrated.. For Siddhartha this was a bit like the last chance saloon so he vowed that he would sit there and not move until he had finally found the answer he was looking for. This decision highlights to us the important fact that we will not find the answer in anyone or anything that is external to us. What he was about to do was to go to the only place where the answer could be realized. He was about to do battle with this thing that we call the mind. Everything he had ever learned, all of the intellectual knowledge he had ever amassed, all of his beliefs, views and opinions were going to be released, so he could enter into a state of meditative absorption that would lead to an irreversible insight into the nature of actuality and thereby realize peace of mind. There would be no tinkly tinkly music playing in the background, no pan pipes, no sounds of dolphins singing. No banging gongs for him to tune into, no chanting of secret mantras. There was nobody leading him on a journey down the garden path and he wasn’t lying on his back with his knees raised and his head supported by a soft cushion. He was seated in an upright position, his spine straight, his legs folded to create a stable base. He was ready to do battle with his conditioned and confused self-biased mind. Comments are closed.

|

Simply Buddhism CourseTalking Dharma CourseContentment

Equinimity Practical kindness Stress Responsibility Worry Death Encouragement Distractions Equinimity revisited Kindness Openness Questioning Secular Awareness Baggage Growth Perfection Anger Forgiveness Angry Wisdom No WorriesA comprehensive and practical guide to a Secular Western approach to Buddhism, Meditation, Life and Actuality. DonatePlease consider making a donation to the

Dharmadatu Buddhist Order & Sangha. |